BRAZIL THE FORGOTTEN ALLY - BRAZIL X USA

8)EXPEDITIONARY FORCE - FEB

WHAT DID YOU DO IN THE WAR ZE CARIOCA?

By Frank Mc D. Cann. University of New Hampshire.

At the Natal meeting, Roosevelt encouraged the idea of Brazil committing troops, telling Vargas that he wanted him with him at the peace table. If Brazil sent its soldiers to fight, it could legitimately claim a larger role in postwar restructuring of the world. After the first war, in which it was an ally but without a combat role, it played a minor part at the conference, and although active in the League of Nations, it had resigned in frustration at not obtaining a permanent council seat in 1926. In addition to international reasons, Vargas likely thought that distracting the military with a foreign campaign would give him some political space in which to develop a populist base with which to preserve the gains of the freshly labelled Estado Nacional.

The dictatorship's opponents quickly regarded a combat role as guarantee that the regime would not outlast the war. They asserted that Brazilians could not fight against tyranny overseas and return to live under it at home. Foreign Minister Oswaldo Aranha saw the war and an expeditionary force as a way to expand Brazil's historic cooperation with the United States into "a true alliance of destinies."

That policy of cooperation had been, Aranha noted, "a source of security" for Brazil, that by giving the United States assurance of Brazil's support in international questions, Brazil could "count on them in [South] American ones." The FEB would, in his view, convince the Americans that Brazil was committed to an alliance "materially, morally, and militarily."

The alliance was his strategy for gaining United States assistance in Brazilian industrialization, which he saw as "the first defense against external and internal danger." He argued that the FEB was the start of a wider collaboration, involving Brazil's total military reorganization. More- over, he did not believe that they could restrict themselves solely to an expeditionary force if they wanted to insure American involvement in other Brazilian military matters, such as development of the navy and air force, and defense of Southern Brazil.

Looking ahead, he believed that Brazil would have to keep its forces mobilized for some time after the peace to help maintain the post-war order. In a cabinet meeting, he asserted that they should work to convince the Americans that "having chosen the road to follow and our companions for the journey we will not after our course or hesitate in our steps." For some Brazilian officers, especially the Escola Militar graduates of the Class of 1917, committing troops would vindicate their not having fought in World War 1; it would also revenge the deaths of friends and colleagues killed in Axis submarine attacks, and, perhaps more importantly, it would increase the army and air force's effective strength and ability to deal with various contingencies.

Among the latter were the strong United States military and naval bases in Northeast Brazil, which the Brazilians wanted to insure that the Americans would vacate after the war; the German immigrant populations in Southern Brazil, which they wanted to be able to control; and, the ever-present fear of Argentina, which was then under a military regime. But the army was not about to ship overseas and trust that all would be well at home or on the frontiers. Its leaders were particularly concerned about Argentina. In July 1943, Minister of War Dutra declared that whatever number of troops went abroad, he wanted an equivalent force left in Brazil "to guarantee sovereignty and the maintenance of order and tranquility here."

Clearly, the home front had to be secure, but to achieve that objective Brazilian leaders would have to pry sufficient weapons from the Americans, who then were struggling to arm their own troops and to produce arms for the A

Washington favored the idea because if the largest Latin American country fought with the Allies, it would enhance the image of the United States as leader of the hemisphere. The Roosevelt administration also hoped that it would make Brazil a pro-American bulwark in South America.

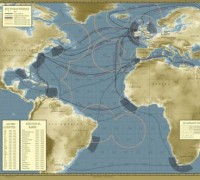

Secretary of State Cordell Hull saw Brazil as a counterweight to Argentina. Both the Brazilians and the Americans adroitly played on the other's worries about Argentina to bolster their policy goals. But, of course, the closer Brazil and the United States became, the more nervous the Argenntnns grew. Some American army leaders were reluctant to accept the Brazilian offer of troops. Their willingness to accommodate the Brazilians was in direct proportion to what they wanted from them. By the end of 1942, the army had its Brazilian air bases and related supply lines through them to North Africa, so why worry about the Brazilians?

A debate took place in American military and diplomatic circles over the merits of accepting or deflecting Brazilian desires. Earlier in 1942, the two governments considered a Brazilian occupation of French and Dutch Guiana and, at Natal (Jan. 1943), Roosevelt suggested to Vargas that Brazil replace Portugal's troops in the Azores and Madeira, so that the Portuguese could reinforce their home defenses. Nothing came of these talks, but after the Natal Conference, it was not if Brazil would fight, but where?

In mid-April 1943, the Brazilian military representative in Washington, General Esteváo Leitáo de Carvalho, told Chief of Staff George Marshall that Brazil wanted to form a three or four division expeditionary Corps, and, in May, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the idea. It is important to emphasize that the expeditionary force was a Brazilian idea, that it resulted from a calculated policy of the Vargas government and not from an American policy to draw Brazil directly into the fighting.