THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

25)THE TROMPKE NETWORK

2 The Trompke Network, the FELIX Organisation and maritime intelligence

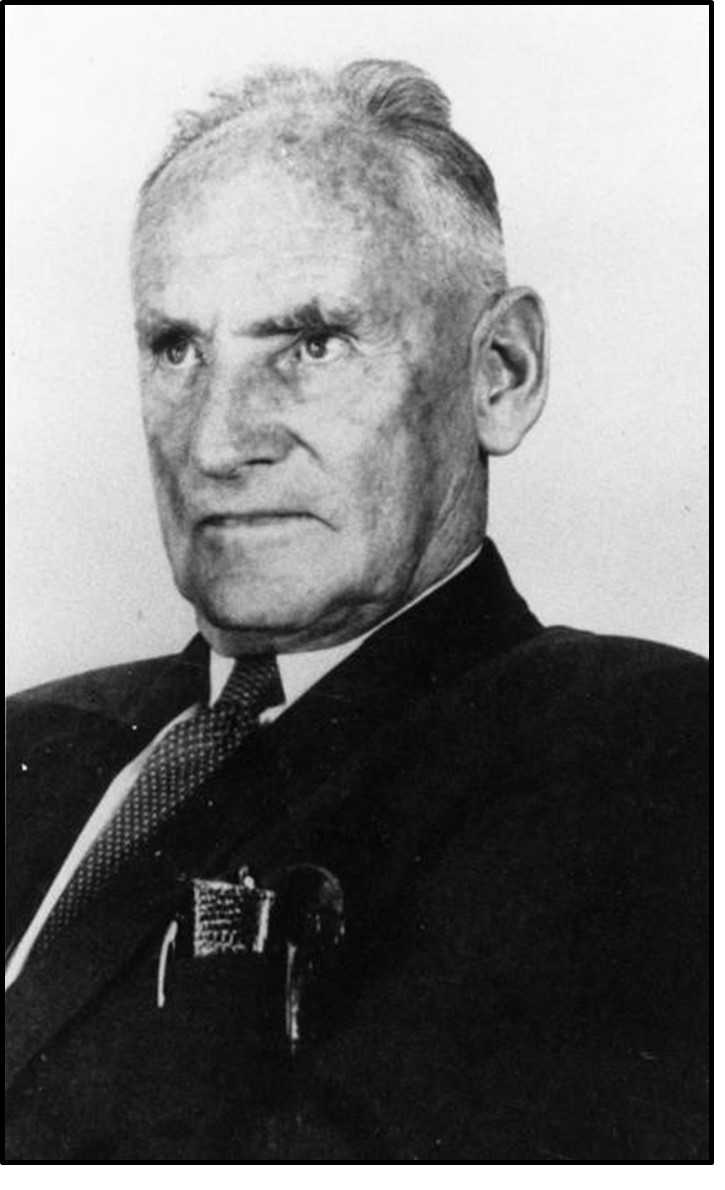

The final, and most enduring contact between the OB and Germany was through a German citizen with the name of Lothar Sittig. Sittig arrived in South Africa well before the war and worked mainly in the agriculture sector in the Cape Province. The Union Government detained him at the Leeuwkop Internment Camp at the outbreak of war. In 1941, however, he escaped with fellow compatriot Nils Pasche.[1] After their arrival in Lourenço Marques in June, Sittig made contact with the German Embassy, and came under the influence of the Consul-General Paul Trompke and a Consul on his staff, Luitpold Werz. Werz was in the service of the German Foreign Office, but primarily ran the German espionage ring in southern Africa during the war.[2]

According to Van der Schyff, the German government was perturbed about the political situation in South Africa, mainly since there was little to no coordination between or action by the anti-war movements. Moreover, previous attempts at establishing a viable link with Afrikaner resistance movements through the Radleys and Rooseboom had proved unsuccessful. Similarly ineffectual were the endeavours made by the German Government through Robey Leibbrandt, who was infiltrated into South Africa during Operation Weissdorn. Leibbrandt in fact only created more problems for the OB, and the National Socialist Rebels – a group that he had formed – played no role in gathering or transmitting naval intelligence.[3]It was the arrival of Olaf Andresen in Lourenço Marques in 1941, that did, however, signal the beginning of a change in the relations between the OB and Germany – particularly in the sphere of espionage. The OB had sent Andresen to Lourenço Marques. Andresen was explicitly despatched to deliver a secret report to Trompke, detailing the existence of the militant Stormjaers organisation within the OB. The Stormjaers, according to this report, were capable of conducting various forms of sabotage, and regularly held secret military training exercises. The report further spoke of armed rebellion, underground resistance, and a possible coup d’état. It concluded that Van Rensburg – the new leader of the OB – knew about, and was actively involved in, the organisation.[4]

Fig 4.3: Lothar Sittig, the infamous FELIX, photographed after the war[5]

Andresen’s report signalled a drastic change in the way in which Germany viewed the OB. Germany considered the OB to have transformed from a cultural to a more militant organisation. According to Sittig, this communiqué prompted Werz to communicate with Van Rensburg directly. Werz subsequently sent Sittig to South Africa to establish contact with the leader of the OB. His assignment was comprised of four key aspects. He had to deliver a personal message from the German government to Van Rensburg and establish direct radio contact with Germany. He was also expected to maintain the secret code for, and act as the principal contact with, Van Rensburg, and report on all political and military matters within South Africa.[6]

In January 1942, Sittig crossed the Mozambican border at Komatipoort, but the SAP arrested him once on South African soil. According to Sittig, an unknown source leaked the complete details of his intended border crossing, leading to his subsequent arrest. He remained at the Baviaanspoort Internment Camp until his escape at the beginning of April,[7] after which he delivered the intended message to Van Rensburg.

The notice read: “The German Government wishes to once more try and establish direct, and reliable, contact between Germany and the Ossewabrandwag, especially with the view of supplying weapons.”[8]

Sittig reported the successful delivery of the message to Van Rensburg with three successive advertisements appearing in the South African newspaper, The Star. It was Pasche, another escaped German internee working at the German Consulate in Lourenço Marques, who picked up the three coded advertisements. Pasche, generally considered a close associate of Sittig, detected a message that read, “Judy, dachshund, lost Commissioner Street Johannesburg, reward will be paid. Phone…” He then informed Werz of Sittig’s success.434

The OB, with the help of Reijer Groeneveld, soon manufactured its own radio transmitter, and used it to establish direct contact with Germany in July 1942. Van Rensburg maintained exclusive, personal control over the radio contact with Germany, despite several attempts by factions within the OB to gain insights and control over this communication channel.[9] Sittig subsequently transmitted Van Rensburg’s reply to Werz, who passed it on to Berlin. The message stated “Van Rensburg asks for intensification of German propaganda for Ossewabrandwag. Stormjaers very active but decisive action impossible without German assistance. Suggestion that coastal town be bombarded [personal suggestion by Sittig].”436

Initially, there were only one-way transmissions between Sittig and Germany. Berlin was, however, concerned about the code and wavelengths that Sittig used in his transmissions to Berlin. This was because they were the same as those used by Rooseboom, and which were considered compromised. After the split occurred with Rooseboom, Sittig requested a new secret code for wireless transmissions to Germany. Pasche personally delivered this new code to Sittig after Werz instructed him to journey to the Union and assist in the transmission of political and military intelligence. The German Foreign Office once more changed the code, with the new code largely based on Morse code with further derivations in the figure groups. Another German agent, Lambertus Elferink, codename HAMLET, delivered the new code to Van Rensburg. Sittig soon began to use it to transmit to Germany. By August 1943, radio contact between Sittig and Germany became more regular, and two-way transmissions occurred two to three times per week.[10]

There are indications that Hans Masser, another escaped German internee, wished to establish a second radio transmitter for sending political and military intelligence to Germany. He would do so through Rooseboom’s connection Wild, thereby circumventing the OB and Sittig network completely. Werz, however, did not receive these proposals with enthusiasm, and the scheme never materialised.[11] Sittig was convinced that the Allied intelligence services never broke the codes which he and Pasche used throughout the war. The available evidence, however, suggests the contrary, since the Allied intelligence services were well aware of Sittig’s existence and transmissions from 1942. The National Archives of the United Kingdom (UK) preserves a number of the decrypted copies of these wireless transmissions, which further reinforces this standpoint.[12]

Fig 4.4: The radio transmitter built by Reijer Groenewald and operated by FELIX[13]

From the outset, the German Foreign Office requested all possible information on shipping movements in southern Africa. The particular data required included the number of ships coming into port, their names whenever possible, their cargo, tonnage, destination and any other information considered of interest.[14] While the reporting of such information from Lourenço Marques was rather straightforward, Sittig had a more difficult time gathering the required information from the South African ports. One particular challenge was that the location from which he regularly transmitted – close to Vryburg in the former Western Transvaal – was quite a distance from the coast. Sittig could thus not conduct personal surveillance of the ports. Instead, he had to rely on second-hand information gathered by OB sympathisers who worked at the South African ports.

The interrogation of Walter Kraizizek, a known German agent, provide some insight into how Sittig obtained much of his naval intelligence. He states that Van Rensburg informed him that Sittig depended on Department of Railways and Harbours (SAR&H) employees who were OB members. These members were strategically positioned at the Durban and Cape Town Harbours to regularly report on shipping movements. Once Van Rensburg received the relevant shipping information, which was sent north via rail once per week, he passed it on to Sittig for transmission to Germany.[15] By the time the information had reached Germany too much time had passed, so the reports had little to no operational value. This is an assessment shared by some contemporary historians.[16] Moreover, when considering that viable two-way transmissions between Sittig and Berlin only commenced in July 1943, the operational value of the shipping information he passed on is questionable. From August 1943, the Seekriegsleitung (SKL) and Befehlshaber der U-Boote (BdU) also ceased to regard South African waters as a viable operational area, particularly since it lacked sufficient sinking potential.[17]

By November 1943, Berlin instructed Sittig to exclusively report on political matters within the Union, as they were concerned that his lengthy transmission might lead to his discovery. FELIX, however, chose to ignore Berlin’s orders somewhat, and continued to transmit military information to Germany. These reports rarely contained matters of naval intelligence. Instead, they imparted information on the movement of South African troops and armament production in the Union. In one particular instance, they relayed particulars about the monthly consumption of potatoes in 48 South African military camps. In return, Germany regularly transmitted sabotage instructions to Sittig. Throughout the first half of 1944, it continued to emphasise the importance of closer collaboration between Sittig and Van Rensburg. The intelligence passed through to Berlin by Sittig continued to prove irrelevant until such time that regular transmissions ceased by the middle of 1944. Its insignificance was predominantly a result of the fact that the tide of the war in the Southern Oceans had drastically turned some months before.[18]

In mid-1942 Sittig made a proposal to Berlin. He suggested that he could transmit shipping intelligence obtained from Cape Town and Durban directly to U-boats operational in the Southern Oceans. Berlin was slow to respond, and by January 1943, Sittig once more pointed out the Achilles heel of these naval operations. He stated that the weak point remained the tenuous link between the source of the intelligence, the wireless station and the operational U-boats – hence his suggestion to transmit shipping intelligence directly to the U-boats. By February, Berlin had confirmed that Sittig would receive a special code in a short time, but by April the scheme was turned down after careful examination proved it impractical.[19]

Hugh Trevor-Roper was an officer who worked at the Radio Security Service (RSS) of the SIS during the war. According to the British historian Edward Harrison, Roper concluded that the naval intelligence supplied by the German espionage networks in southern Africa was not valuable enough to assist the U-boats operating in South African waters.[20] Moreover, Sittig’s proposal seems impractical, particularly since the BdU, and Dönitz in particular, maintained daily contact with the operational Uboats, and passed on the relevant intelligence reports from the B-Dienst when applicable.[21]

Between 1942 and 1943, Sittig made several appeals to Berlin for the transference – by U-boat – of weapons for sabotage, several wireless sets and spare parts, a qualified wireless technician, as well as a large sum of money for sustenance purposes. After delivery, the U-boat would return to Germany with a consignment of diamonds and a representative from the OB to cooperate with the authorities in Berlin, especially with regard to broadcasting propaganda back to the Union. Heimer Anderson was initially earmarked to travel to Germany as the OB representative, largely due to his close personal relationship with Van Rensburg and his involvement in the Sittig transmissions. By September 1943, Sittig had suggested a number of possible points along the South African coastline where the transfer could take place. He somewhat optimistically informed Berlin that the area between Mossel Bay and George was particularly well suited as most of the local inhabitants were OB supporters.[22] Sittig eventually convinced Berlin that the best location for the landing by a German submarine would be at Cape St Francis. This area is situated near Port Elizabeth, at a spot close to the mouth of the Seekoei River. Despite lengthy transmissions regarding the above, nothing ever came of the scheme, and by the end of 1943, Berlin ceased to regard it as a viable operation.[23]

Fig 4.5: The secret rendezvous location near Cape St Francis[24]

Sittig, however, remained somewhat sceptical of the real value of his transmissions to Germany. He was confident that Radio Zeesen utilised the political matters he reported on for propaganda purposes. But he was less confident of the value of the military matters he reported on. This was particularly the case since he was convinced that Adm Wilhelm Canaris buried the Abwehr intelligence reports emanating from southern Africa to such an extent that the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht came to distrust the source of intelligence. He did, however, maintain that the value of the military intelligence passed on to Germany by the OB was high. According to Sittig, several members of both the Stormjaers and the OB served in the Union Defence Force (UDF) and SAP and instinctively passed on valuable military intelligence for transmission to Germany.[25] Van Rensburg, however, prevented the transmission of military intelligence that would directly endanger South African lives, despite several objections to the contrary from within the OB and from Germany. This very matter formed the basis of the disagreement between Van Rensburg and Rooseboom mentioned previously – and the eventual disillusionment of Pasche. According to Sittig, certain OB members continued to hope for direct German military intervention in South Africa. Germany, however, never contemplated this, and Van der Schyff maintains that Van Rensburg would have militantly opposed any such attempt.[26]

It is incorrectly stated by Van der Schyff that the final contact between the OB and Germany occurred in January 1944 when Groeneveld received a last non-encoded message from Germany. It was only by mid-1944 that Groeneveld received the final message from Berlin, though by this stage of the war the value of Sittig and his political reports had diminished to such an extent that it was of no real use to Germany.[27] A British Security Service (MI5) officer working on the Sittig case perhaps has the final word on the operational effectiveness of his intelligence reports during the war. He states that:

The most surprising fact with regard to the whole organisation is that … Sittig and his agents have produced little information of real value. It is almost inconceivable to believe that anywhere else in the world, German agents as well-placed as Sittig and his associates, in close contact with an opposition leader of high standing, would not produce information which would be of vital interest to the Abwehr. Sittig has produced occasional inaccurate shipping information and political gossip which could be culled from the columns of any South African newspaper.[28]

[1] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. L. Sittig.

[2] TNA, KV 2/202, Elferink, Lambertus. 152a – Interim Report on WERZ, Luitpold, 31 Oct 1945; Fokkens, ‘Afrikaner Unrest within South Africa during the Second World War’, p. 140.

[3] TNA, KV 2/925, Leibbrandt, Robey. 67a – From Col. Webster attaching replies to questionnaire, copies of photograph, memorandum re LEIBRANDT’s activities, 1 Jun 1942. For more information on Leibbrandt see Visser, OB: Traitors or Patriots?, pp. 54-66; TNA, KV 2/925, Leibbrandt, Robey; TNA, KV 2/924, Leibbrandt, Robey; Strydom, Vir Volk en Führer.

[4] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. L. Sittig; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L.

Sittig Collection. Kontak tussen die Ossewabrandwag en die Duitse Regering, 1942-1944.

[5] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Photo Collection. F01069_5 – L. Sittig.

[6] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. Kontak tussen die Ossewabrandwag en die Duitse Regering, 1942-1944.

[7] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 109

[8] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. Kontak tussen die Ossewabrandwag en die Duitse Regering, 1942-1944. The original Afrikaans text reads: “Die Duitse Regering wil nog eenkeer op die noodsaaklikheid van ʼn betroubare, direkte verbinding tussen Duitsland en die Ossewabrandwag verwys met die oog op die lewering van wapens.” 434 NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. L. Sittig.

[9] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Transkripsies/Bandopname. R. Groeneveld; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. Kontak tussen die Ossewabrandwag en die Duitse Regering, 1942-1944. 436 Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 110.

[10] TNA, KV 2/202, Elferink, Lambertus. 152a – Interim Report on WERZ, Luitpold, 31 Oct 1945; NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. Lyste met kodes, ongedateer. NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. Kontak tussen die Ossewabrandwag en die Duitse Regering, 1942-1944.

[11] TNA, KV 2/941, Rooseboom, Hans. 44a – Copy of Interim Report on Walter Paul Kraizizek, 31 Oct 1945.

[12] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, L. Sittig Collection. 3(a) – N.O. Pasche, 12 Aug 1986; TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/ Nils PAASCHE. 79a – Copy of First Report on German Espionage in the Union of

South Africa, 25 Sept 1943; TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/ Nils PAASCHE. 121b – Copy of Second Report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 27 Nov 1943; TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/ Nils PAASCHE. 194a – Extracts from Third Report German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 May 1944.

[13] NWU, RAM Div, OB Archive, Photo Collection. M0011 – Radiosender.

[14] TNA, KV 2/202, Elferink, Lambertus. 152a – Interim Report on WERZ, Luitpold, 31 Oct 1945.

[15] TNA, KV 2/940 – Kolb, Hubert. 55a – Interim Report on Walter Paul Kraizizek.

[16] Harrison, ‘On Secret Service for the Duce’, pp. 1348-1349; Fedorowich, ‘German Espionage and British Counter-Intelligence in South Africa’, p. 225.

[17] TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/ Nils PAASCHE. 79a – Copy of First Report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 Sept 1943.

[18] TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/Nils PAASCHE. 194a – Extracts from Third Report German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 May 1944.

[19] TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/Nils PAASCHE. 79a – Copy of First Report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 Sept 1943; TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/ Nils PAASCHE. 121b – Copy of Second Report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 27 Nov 1943; Fedorowich, ‘German Espionage and British Counter-Intelligence in South Africa’, p. 228.

[20] Harrison, ‘British Radio Security and Intelligence, 1939-43’, p. 88.

[21] The B-Dienst was the cryptographic section of the Naval High Command, which helped to monitor Allied radio traffic and hence tried to decipher these messages. See Faulkner, ‘The Kriegsmarine, Signals Intelligence and the Development of the B-Dienst’, pp. 521-546.

[22] TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/Nils PAASCHE. 79a – Copy of First Report on German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 Sept 1943. For more on the apparent contact between South Africans and U-boats during the war see the highly dubious Mahncke, U-Boats & Spies in Southern Africa.

[23] TNA, KV 2/939, Lothar SITTIG/Nils PAASCHE. 194a – Extracts from Third Report German Espionage in the Union of South Africa, 25 May 1944.

[24] Author’s personal photo collection.

[25] Also see Shear, ‘Colonel Coetzee's War’, pp. 222-248.

[26] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, pp. 110-114.

[27] Van der Schyff, Die Ossewa-Brandwag en die Tweede Wêreldoorlog, p. 114.

[28] TNA, KV3/10. German Espionage in South Africa, 1939-1945. German intelligence activities in South Africa during the Second World War.