THE AXIS AND ALLIED MARITIME OPERATIONS AROUND SOUTHERN AFRICA 1939 1945 - WAR ON SOUTHERN AFRICA SEA

22)UBOAT OFFENSIVE OFF S AFR

.3 The German U-boat offensives off the South African coast

In February 1941, after the German sinking results in the North Atlantic diminished considerably, the Befehlshaber der U-Boote (BdU) decided that the time for sending a number of type IX U-boats to operate in the South Atlantic was opportune. These submarines were to operate predominantly off Freetown. At this stage of the war, Karl Dönitz argued that the BdU focus all of their energy on the prosecution of the U-boat war in the North Atlantic, and not on far-flung operations in the remote corners of the globe. In his memoirs, however, Dönitz categorically stated that Hitler and the political leadership of Germany failed to understand this strategy, and in essence, the basic fundamentals of U-boat warfare.[1] The BdU also made use of secret replenishment points in the Central Atlantic, particularly ‘Andalusien’. These secret replenishment points allowed for surface supply ships to rendezvous with U-boats and replenish their ammunition and logistical stores. In a greater sense, the replenishments enabled the Uboats to undertake two successive patrols in an operational area without returning to their bases in the Bay of Biscay, which could be as distant as 2,800 miles.

The system of double patrols proved extremely effective with some seven Uboats sinking more than seventy-four ship in the first half of 1941. During this period U69 (Metzler) travelled south along the African coast and mined the ports of Lagos and Takoradi in the Gulf of Guinea, after which the mines claimed several victims. This prompted the British Admiralty to close these ports temporarily. During the months of May and June, a total of 119 ships (635,635 tons) were sunk in the North Atlantic and the operational area off Freetown. Between July and August, the sinking results off Freetown dropped considerably, as there were only eight to twelve U-boats operational in this area at that time. The heavy losses of merchant vessels off Freetown persuaded the British Admiralty to reduce Allied shipping activity in the area to a minimum. The Admiralty would also redirect traffic to the relative safety of the Pan-American safety zone, an area then still closed to U-boats for political reasons. The very dense American commercial shipping off Freetown further complicated U-boat operations in the area, as they were naturally not allowed to attack neutral shipping. Following the loss of a unidentified surface supply ship, Dönitz redeployed the mainstay of his U-boats to operations in the North and Eastern Atlantic. Here, the merchant sinking potential continued to be substantial.[2]

Fig 3.2: Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz[3]

By October, only two U-boats remained operational off Freetown with enough fuel left to continue operations until forced to resupply from the Atlantis and Python (Lüders). After first operating off the coast of Freetown, U-126 (Bauer) subsequently sailed to the coast of Guinea, while U-68 (Merten) proceeded to Walvis Bay via Ascension and St. Helena. On its way to South-West Africa, U-68 sank the British tanker Darkdale (8,145 tons) off St. Helena, as well as a further two British merchantmen, the Hazelside (5,279 tons) and Bradford City (4,925 tons). The U-boat arrived off Walvis Bay on 11 November and observed no sea traffic. On 13 November, it sailed northwards and rendezvoused with the Atlantis south of St. Helena Island for replenishment. The Atlantis thereafter travelled northwards to resupply U-126 to the north-west of Ascension Island. On 22 November, however, the Atlantis was surprised en route and subsequently sunk by the cruiser HMS Devonshire. The survivors from the Atlantis were rescued by U-126. The Python, along with U-124 (Mohr) and U-129 (Clausen) also received instructions to assist with transporting the survivors, despite all being initially earmarked for an operation in Cape Town waters. Two days previously, the Python had resupplied U-124 and U-129 near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago in the central equatorial area of the Atlantic Ocean. On her way to the rendezvous, U-124 also sank the cruiser HMS Dunedin (4,850 tons).[4]

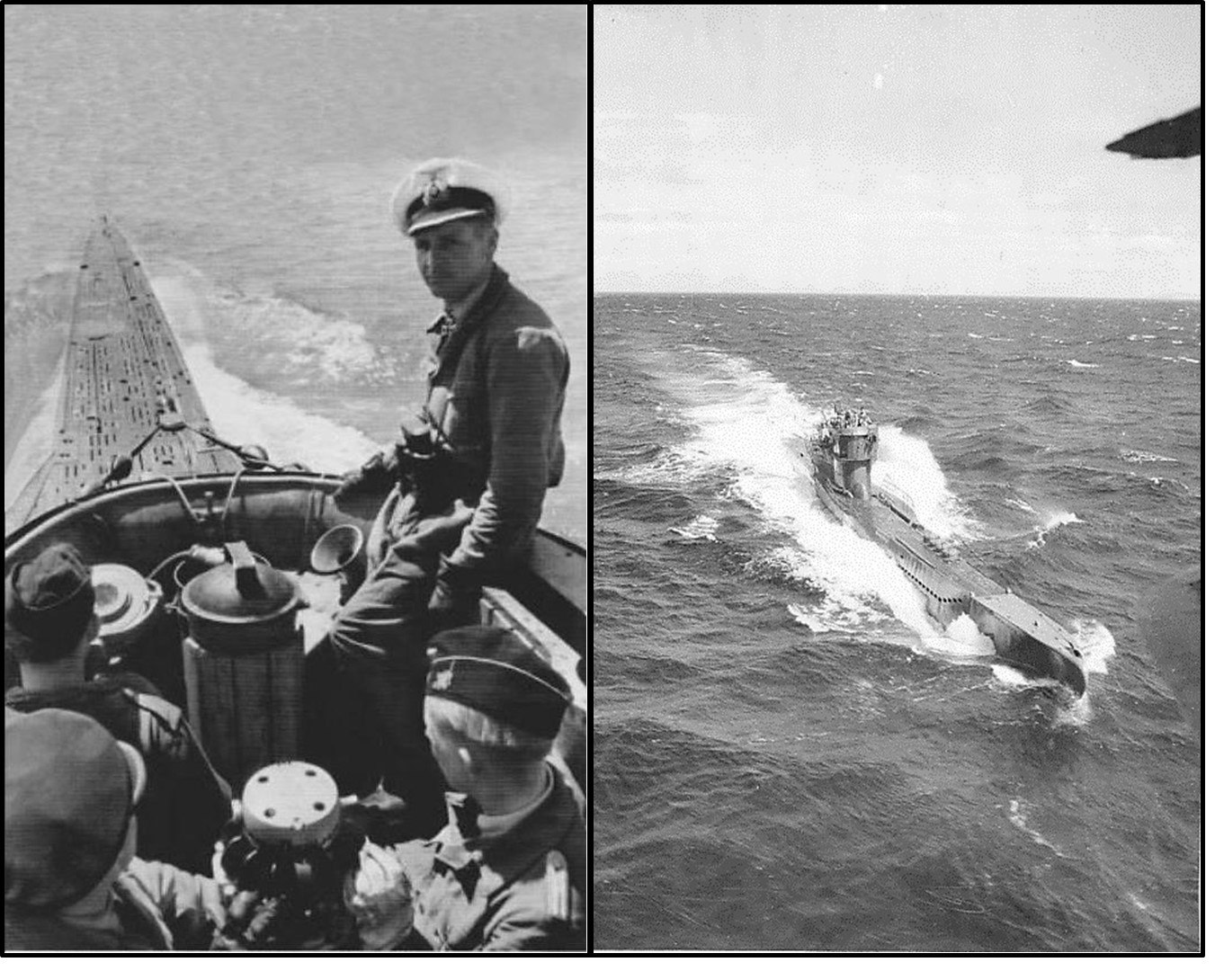

Fig 3.3: German U-boat crew assisting the survivors of a sunken merchantman[5]

The survivors of Atlantis were transferred to the Python during the rendezvous with U-126. The Python was then ordered to remain in the South Atlantic as she had enough fuel and provisions to support the remaining four operational U-boats in the area. The BdU decided that U-124, U-129, U-68 – all of the type IX class – and U-A (Eckermann) should launch a surprise operation in the waters off Cape Town, after replenishing their supplies from the Python. This operation, however, came to nothing. On the afternoon of 1 December, after having resupplied U-68, and while busy resupplying U-A, Python was surprised and successfully engaged by HMS Dorsetshire after Ultra intelligence had pinpointed her location. While U-68 and U-A managed to escape the attack from HMS Dorsetshire by diving, the crew of the Python opted to scuttle the ship.

The attacks on the Atlantis and Python, both while they were resupplying U-boats, were a matter of grave concern to the BdU and the SKL. They were convinced that direction-finding alone could not have guided the British warship to the exact location of the German supply vessels, though the raider code was never broken by the Allies. The crews of the Atlantis and Python were subsequently transferred to the four U-boats, whereafter they started their return journeys to the Bay of Biscay. During the return trip, U-124 managed to sink the American merchantman Sagadahoc (6,275 tons). The four U-boats then rendezvoused close to the Cape Verde Islands with four Italian submarines that had sailed from Bordeaux. These were the Pietro Calvi (Olivieri)[6], Giuseppe Finzi (Giudice)[7], Enrico Tazzoli (di Cossato)[8] and Luigi Torelli (De Giacomo)[9]. The Italian submarines helped to transport the crews of the Atlantis and Python to their bases in the Bay of Biscay. All eight submarines had arrived at their respective bases by the end of December.

The destruction of the Atlantis and Python meant that surface vessels could no longer supply U-boats in the South Atlantic, which necessitated the temporary shelving of all plans for offensive operations in the waters off Cape Town. At this stage, it was also more economical to employ U-boats in operations off the American seaboard. The American entry into the war had incontrovertibly opened several new avenues of attack with the promise of rich merchant spoils and much shorter operational distances.[10]

The sinking results of the U-boats operating in the North Atlantic off the American seaboard, as well as the Caribbean, had, however, decreased somewhat substantially. The BdU concluded in July 1942 that the reduction had occurred to such an extent that it was no longer worthwhile considering these areas as the main theatre for sustained Uboat operations. This was mainly due to the introduction of Allied convoys and effective A/S measures in these waters. The BdU hence adopted a policy of pursuing U-boat operations in distant waters, provided that the sinking results and prospects of success in these areas justified the economic use of force in such operations. They had the added advantage of coercing the Allies into spreading their A/S forces across the globe to engage the U-boats wherever they appeared. The main weight of the U-boat operations thereupon shifted to the mid-Atlantic. The renewed focus was on attacking convoys to and from Britain, as these areas were devoid of good air cover.

At least thirty new U-boats were delivered per month during July, August and September 1942, mainly due to the clearing of arrears in U-boat construction from the previous year. The arrival of these new U-boats enabled the BdU to promptly resume operations against Allied convoys in the North Atlantic. The increase in forces furthermore allowed for U-boats to deliver surprise attacks in distant waters. The first three areas selected for the sporadic subsidiary operations were the waters off Trinidad in the Caribbean, Freetown, and a sudden onslaught in the waters off Cape Town. Dönitz had hoped to cause a diversionary effect with these distant interventions, pressurising the Allies into splitting their defensive forces between protecting the North Atlantic, the Eastern American seaboard, the Caribbean and the extensive African coast bordering the Indian and Atlantic oceans. The Japanese submarine offensive in the Mozambican Channel had naturally also contributed to this diversionary effect.[11]

Fig 3.4: A German U-boat refuelling from a supply ship in the South Atlantic[12]

By July 1942 the waters off Cape Town were still considered virgin waters by the BdU. The area had remained devoid of any noteworthy submarine activity, apart from U-68’s brief foray to the coast of South West Africa in November 1941. Prior to 1942, the BdU also did not favour sending single U-boats to operate off the southern African coast as their independent actions would alert the Allies and force them to adopt stringent A/S measures in these waters. Moreover, a single submarine operating in the Cape Town waters would not reach satisfactory sinking results needed to justify its deployment in such distant reaches. The BdU further realised that an operation off Cape Town could only materialise once sufficient numbers of U-boats were available to launch a concentrated attack and sustain it for an indefinite period to allow for satisfactory sinking results. Dönitz and the BdU, however, maintained that the primary focus of the U-boat war remained the sinking of Allied merchant shipping, and not merely the tying down of Allied forces through diversionary U-boat attacks.[13]

|

Class |

Type IXC |

Type IXD2 |

|

Displacement |

1,540 tons |

2,150 tons |

|

Crew |

48-56 men |

55-63 men |

|

Speed (Surface) |

18.3 knots (33.8 km/h) |

19.2 knots (35.5 km/h) |

|

Speed (Submerged) |

7.3 knots (13.5 km/h) |

6.9 knots (12.7 km/h) |

|

Surface Range |

13450 miles @ 10 knots |

23700 miles @ 12 knots |

|

Submerged Range |

63 miles @ 4 knots |

57 miles @ 4 knots |

|

Armament |

6 × Torpedo tubes 21 torpedoes 1 × 10.5 cm deck gun 1 × 3.7 cm AA gun 1 × 2.0 cm AA gun |

6 × Torpedo tubes 24 torpedoes 1 × 10.5 cm deck gun 1 × 3.7 cm AA gun 1 × 2.0 cm AA gun |

Table 3.7: Statistical data on German U-boats operational in South African waters[14]

Between October and November, the Allies committed the majority of their escort fleets to the protection of the North African and Mediterranean waters. This action was the result of the unfolding campaign in North Africa, which further enticed Dönitz to strike towards the proverbial ‘soft underbelly’ of South Africa. The BdU, however, appreciated the logistical complications associated with operations in such distant waters, especially after the loss of the Atlantis and Python. As early as 1941, it experimented with the use of supply U-boats (milch cows[15]) in provisioning submarines on remote operations. Furthermore, by August, the BdU had a large enough number of the type IXC U-boats at its disposal, which exponentially increased the duration of U-boat operations. Hence, when operating in conjunction with the milch cows, the offensive employment of U-boats now extended to areas previously devoid of any sustained U-boat operations. Dönitz furthermore hoped to extend U-boat operations to cover the African ports in the Indian Ocean, but accepted that this would only be possible by October when the new type IXD2 U-boats came into service (see Table 3.7).[16]

Fig 3.5: German U-boats operational in the Southern Oceans, circa 1941[17]

By August, the BdU had earmarked four type IXC U-boats for the surprise onslaught in the Cape Town waters. The Eisbär group was ordered to strike a decisive blow at shipping in the waters off Cape Town during October. The wolf pack consisted of U-68 (Merten), U-172 (Emmermann), U-504 (Poske) and U-156 (Hartenstein), and was accompanied by the milch cow U-459 (Wilamowitz-Möllendorf). Dönitz argued that the U-boats were to remain in the operational area off Cape Town until approximately the end of October. The aim was to disrupt and destroy merchant shipping and achieve the necessary sinking results required to make such a far-flung operation a success. A fresh batch of U-boats would then relieve the Eisbär group and continue operations in this area. After the Eisbär boats had sailed for Cape Town from their base at Lorient in late August, they had to cover approximately 6 000 sea miles before they reached the operational waters off Cape Town.[18]

To ensure maximum surprise, the SKL required the U-boats to remain undetected for their entire voyage to Cape Town. The SKL argued throughout September that the most important factor to consider was the strategic effect which the Eisbär group would achieve. This included throwing the traffic off the coast of South Africa into such a state of confusion that sea traffic around the Cape of Good Hope would halt. South African ports would then become clogged with ever-increasing numbers of merchant shipping seeking shelter. Be that as it may, only surprise could ensure this strategic effect. The BdU and Dönitz, however, argued that the most important factor to consider during the entire operation would be the actual sinking results achieved by the Eisbär pack. Dönitz thus argued that the Eisbär boats should attack shipping during their entire approach voyage to Cape Town. The ultimate goal of the operation, as Dönitz argued, was a short, sharp, U-boat offensive, which could yield the highest possible sinking results in the shortest possible time without incurring too many U-boat losses. The SKL and BdU eventually reached a compromise and decided that the U-boats could attack merchant shipping during their approach voyage to Cape Town, but only between the equator and 5° south.[19] Dönitz’s reply to this debacle was that the strategists were once again out to “tickle” the enemy. To this he added, “Unfortunately I do not know of a single case, when an enemy had been tickled to death.”[20]

During their voyage south, the Eisbär boats attempted – albeit unsuccessfully – to attack convoy SL 119 which was making its way to Freetown. While each U-boat continued its journey south independently, the wolf pack travelled in an extended harrow bone formation spread out across a vast distance. In this way, it was able to remain undetected and able to increase the chances for opportunistic attacks against Allied shipping. The U-boats were to replenish their supplies from U-459 on 20 September at a position approximately 20° south of the equator. While en route to rendezvous with U-459, U-156 sank the British troopship Laconia (19,965 tons) on 12 September. This chapter does not deal with the sinking of the Laconia, but it is of interest to note that Dönitz ordered the remainder of the Eisbär boats to assist in rescuing the survivors. Only once two Vichy French boats were despatched to help assist with the rescue of survivors, were the U-boats recalled from the rescue operation.[21]

Fig 3.6: U-156 and U-507 assisting survivors from the Laconia, 15 Sept 1942[22]

On 16 September, an indiscriminate Allied bombing attack damaged U-156 to such an extent that the BdU recalled it from the Eisbär group. The BdU rapidly replaced U-156 with U-159 (Witte) as the U-boat was then operational in the equatorial area off the mouth of the Congo River. The Eisbär boats rendezvoused with U-459 between 22 and 24 September to the south of St Helena, where each U-boat successfully replenished its supplies. This included 100-110 tons of fuel, four tons of lubricating oil and enough food stocks and other essential supplies for 30 days. The remainder of the U-boats’ journey south occurred without incident, and the Eisbär group arrived off the coast of Cape Town during the first week of October.[23]

On the night of 6/7 October 1942, Emmermann managed to infiltrate his U-boat successfully into Cape Town harbour’s roadstead. After conducting a reconnaissance, he found it to be empty of Allied merchant vessels. The BdU had initially ordered the Eisbär group to commence their attack on the shipping off Cape Town on the night of 8/9 October, but after receiving Emmermann’s report, it was decided to postpone the attack to the night of 10/11 October. In the meantime U-68 trailed several steamers while steadily approaching Cape Town harbour. During the evening of 7/8 October, Merten received Emmermann’s report stating that the roadstead was empty. Merten forthwith informed the BdU of the changing tactical situation in the waters off Cape Town. At that point, the U-boats were authorised to launch their attacks at midnight on 8 October. Local intelligence sources indicated that Cape Town harbour retained up to 50 ships anchored at any time, and the BdU believed that a surprise attack by two U-boats could achieve more than the desired results, after which the remaining U-boats were free to take offensive action. The U-boat commanders and the BdU were furthermore convinced that the South African defences would be caught totally unaware, for it seemed that neither their wireless transmissions nor their presence was detected.[24]

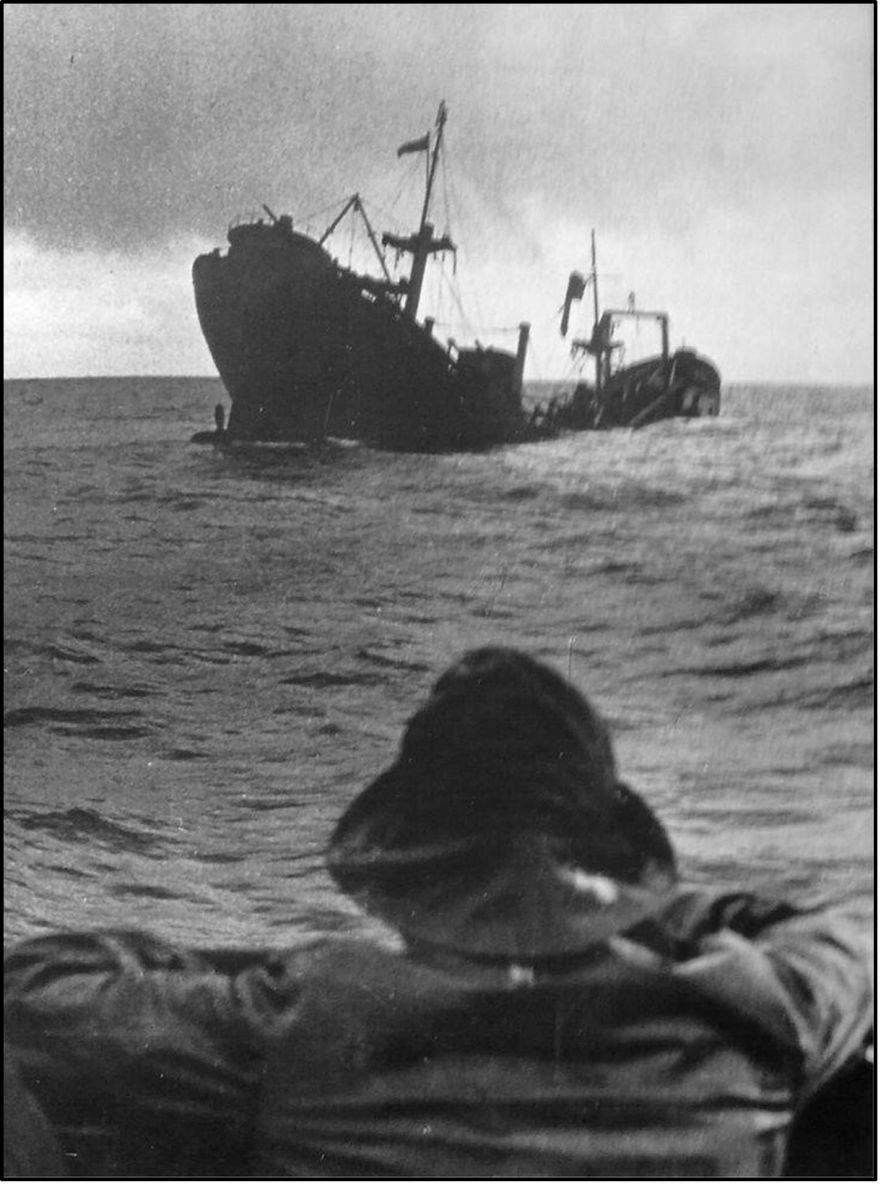

Fig 3.7: A U-boat watching its target sink in the Southern Oceans[25]

The resulting U-boat offensive succeeded in sinking 13 merchantmen within the first three days of operations. They were the Chikasaw City (6,196 tons), Firethorn (4,700 tons), Boringia (5,821 tons), City of Athens (6,558 tons), Clan Mactavish (7,631 tons), Sarthe (5,271 tons), Swiftsure (8,206 tons), Gaasterkerk (8,679 tons), Koumoundouros (3,598 tons), Examelia (4,981 tons), Coloradan (6,557 tons), Belgian Fighter (5,403 tons) and Orcades (23,456 tons).[26] The U-boat pickings were initially child’s play. But as the surprise gained during the initial attack started to dwindle, and the South African and Allied counter-measures were activated, Dönitz ordered the Eisbär group to extend their operational area to as far afield as Port Elizabeth and Durban.

The initial attacks on the merchant shipping off Cape Town were facilitated by the fact that the majority of South African lighthouses were still functioning at full capacity, while most merchantmen sailed independently around the South African coast. Because of this complacency present in South Africa, very few A/S vessels and aircraft were operational off the coast of South Africa by October. Bad weather, however, set in on 13 October, which forced the submarines further afield, with U-159 venturing as far as 40° south in search of merchant vessels.[27] Shortly after the commencement of Operation Eisbär, U-68 and U-172 were forced to commence their return voyage. This occurred even before they had managed to fire all of their torpedoes.[28] The BdU subsequently decided that U-504 and U-159 would move further south and south-east of Cape Town where they managed to sink several more vessels over the period of 13 October to 3 November.[29] Its targets included the Empire Nomad (7,167 tons), Empire Chaucer (5,970 tons), City of Johannesburg (5,669 tons), Anne Hutchinson (7,176 tons), Ross (4,978 tons), Laplace (7,327 tons), La Salle (5,462 tons), Empire Guidon (7,041 tons), Reynolds (5,113 tons) and the Porto Alegre (5,187 tons). After these attacks, U-504 and U-159 also had to turn back to their bases in France. During their return voyages, the Eisbär boats succeeded in sinking a further three merchantmen: the Aldington Court (4,891 tons), Llandilo (4,966 tons) and the Star of Scotland (2,290 tons) (see Table 3.8).[30]

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

7 Oct 1942 (U-172) |

Chikasaw City |

6,196 |

Amer. |

34⁰ 05'S; 17⁰ 16'E |

|

2 |

7 Oct 1942 (U-172) |

Firethorn |

4,700 |

Pan. |

34⁰ 10'S; 17⁰ 07'E |

|

3 |

7 Oct 1942 (U-172) |

Koumoundouros |

3,598 |

Greek |

34⁰ 00'S; 17 ⁰30'E |

|

4 |

7 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Boringia |

5,821 |

Brit. |

35⁰ 09'S; 16⁰ 32'E |

|

5 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Clan Mactavish |

7,631 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 53'S; 16⁰ 45'E |

|

6 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-68) |

Sarthe |

5,271 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 50'S; 18⁰ 40'E |

|

7 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-68) |

Swiftsure |

8,206 |

Amer. |

34⁰ 40'S; 18⁰ 25'E |

|

8 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-68) |

Gaasterkerk |

8,679 |

Dutch |

34⁰ 20'S; 18⁰ 10'E |

|

9 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-68) |

Examelia |

4,981 |

Amer. |

34⁰ 52'S; 18⁰ 30'E |

|

10 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

City of Athens |

6,558 |

Brit. |

33⁰ 40'S; 17⁰ 03'E |

|

11 |

9 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Coloradan |

6,557 |

Amer. |

35⁰ 47'S; 14⁰ 34'E |

|

12 |

9 Oct 1942 (U-68) |

Belgian Fighter |

5,403 |

Belg. |

35⁰ 00'S; 18⁰ 30'E |

|

13 |

10 Oct 1942 (U-172) |

Orcades |

23,456 |

Brit. |

35⁰ 51'S; 14 ⁰ 40'E |

|

14 |

13 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Empire Nomad |

7,167 |

Brit. |

37⁰ 50'S; 18⁰ 16'E |

|

15 |

17 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

Empire Chaucer |

5,970 |

Brit. |

40⁰ 20'S; 18⁰ 30'E |

|

16 |

23 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

City of Johannesburg |

5,669 |

Brit. |

33⁰ 20'S; 29⁰ 30'E |

|

17 |

26 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

Anne Hutchinson |

7,176 |

Amer. |

33⁰10'S; 28⁰ 30'E |

|

18 |

29 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Ross |

4,978 |

Brit. |

38⁰ 51'S; 21⁰ 40'E |

|

19 |

29 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

Laplace |

7,327 |

Brit. |

40⁰ 33'S; 21⁰ 35'E |

|

20 |

29 Oct 1942 (U-159) |

La Salle |

5,462 |

Amer. |

40⁰ 00'S; 21⁰ 30 'E |

|

21 |

31 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

Empire Guidon |

7,041 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 40'S; 34⁰ 20'E |

|

22 |

31 Oct 1942 (U-504) |

Reynolds |

5,113 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 00'S; 35⁰ 10'E |

|

23 |

3 Nov 1942 (U-504) |

Porto Alegre |

5,187 |

Braz. |

35⁰ 27'S; 28⁰ 02'E |

|

24 |

31 Oct 1942 (U-172) |

Aldington Court |

4,891 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 20'S; 02⁰ 10'W |

|

25 |

2 Nov 1942(U-172) |

Llandilo |

4,966 |

Brit. |

27⁰ 03'S; 02⁰ 59'W |

|

26 |

13 Nov 1942 (U-159) |

Star of Scotland |

2,290 |

Amer. |

26⁰ 30'S; 00⁰ 20'W |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

26 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

170,294 tons |

||||

Table 3.8: Merchantmen lost to the Eisbär Group, Oct-Nov 1942[1]

A batch of the new type IXD2 U-boats, captained by experienced commanders, was commissioned between August and September. This allowed Dönitz’s hope for U-boat operations to extend to cover the African ports in the Indian Ocean, to be realised. The BdU decided that these boats relieve the Eisbär group to maintain constant pressure on the shipping off South Africa. The first of the U-boats, U-179 (Sobe) sailed by mid August, and without the knowledge of the BdU, it caught up to and joined the Eisbär group in the waters off Cape Town. On 8 October, as the Eisbär boats launched their attacks, U-179 sank the Pantelis (3,845 tons). The fate of U-179 was, however, sealed. Shortly after, depth charges were dropped from the British destroyer HMS Active and sank the U-boat. For the remainder of the Second World War, the BdU believed that U179 had been sunk by Allied bombers off the coast of Ascension Island, while on her return voyage to Lorient. Three more type IXD2 U-boats, U-178 (Ibbeken), U-181 (Lüth) and U-177 (Gysae), left Lorient between 8 and 17 September and arrived in the waters off Cape Town at the end of October. During the following six weeks, they operated off the east coast of South Africa and travelled as far as Lourenço Marques in the Mozambique Channel.[32]

These type IXD2 U-boats collectively formed part of the first U-cruiser operation in the Southern Oceans and were extremely successful during their deployment (see Table 3.9). They managed to sink 25 merchant ships: Aegeus (4,538 tons), Mendoza (8,233 tons), East Indian (8,159 tons), Trekieve (5,244 tons), Hai Hing (2,561 tons), Plaudit (5,060 tons), K.G. Meldahl (3,799 tons), Excello (4,969 tons), Louise Moller (3,764 tons), Gunda (2,241 tons), Scottish Chief (7,006 tons), Corinthiakos (3,562 tons), Pierce Butler (7,191 tons), Alcoa Pathfinder (6,797 tons), Mount Helmos (6,481 tons), Dorington Court (5,281 tons), Jeremiah Wadsworth (7,176 tons), Evanthia (3,551 tons), Nova Scotia (6,796 tons), Cleanthis (4,153 tons), Llandaff Castle (10,799), Amarylis (4,328 tons), Saronikos (3,548 tons), Empire Gull (6,408), and Sawahloento (3,085 tons).[33] The British Auxiliary Cruiser Nova Scotia had transported 800 Italian civilian internees on board, and fearing a repeat of the Laconia incident, the BdU ordered the U-boats not to attempt a rescue operation. By mid-November, the SKL obligated all remaining German submarines off the South African coast to return to the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Here they would be expected to attack Allied shipping after the successful American landings in North Africa during Operation Torch.[34]

During October, the Italian submarine Ammiraglio Cagni (Liannazza)[35] travelled from its Mediterranean base to its operational area to the south-west coast of Africa and the waters off Cape Town. On 29 November the Ammiraglio Cagni sank the Argo (5,550 tons), whereafter it had to start its return journey to Bordeaux. During this voyage, the submarine was successfully provisioned by U-459, after which it operated off the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago before returning to base in February 1943. During the period between 7 October and 14 December 1942, eight U-boats and one Italian submarine sank 53 merchantmen, for the loss of only one U-boat. The sinking results were thus an approximate 5.88 merchant vessels sunk per U-boat, with a striking 314,419 tons of merchant shipping lost off the South African coast. The BdU was thus able to prove to the SKL that operations as far south as the waters off the South African coast were not only possible, but could yield good sinking results.[36]

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

8 Oct 1942 (U-179) |

Pantelis |

3,845 |

Greek |

34⁰ 20'S; 17⁰ 50'E |

|

2 |

31 Oct 1942 (U-177) |

Aegeus |

4,538 |

Greek |

32⁰ 30'S; 16⁰ 00'E |

|

3 |

1 Nov 1942 (U-178) |

Mendoza |

8,233 |

Brit. |

29⁰ 20'S; 32⁰ 13'E |

|

4 |

3 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

East Indian |

8,159 |

Amer. |

37⁰ 23'S; 13⁰ 34'E |

|

5 |

4 Nov 1942 (U-178) |

Trekieve |

5,244 |

Brit. |

25⁰ 46'S; 33⁰ 48'E |

|

6 |

4 Nov 1942 (U-178) |

Hai Hing |

2,561 |

Norw. |

25⁰ 55'S; 33⁰ 10'E |

|

7 |

8 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Plaudit |

5,060 |

Pan. |

36⁰ 00'S; 26⁰ 32'E |

|

8 |

10 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

K.G. Meldahl |

3,799 |

Norw. |

34⁰ 59'S; 29⁰ 45'E |

|

9 |

13 Nov 1942 (U-178) |

Louise Moller |

3,764 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 50'S; 35⁰ 54'E |

|

10 |

13 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Excello |

4,969 |

Amer. |

32⁰ 23'S; 30⁰ 07'E |

|

11 |

19 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Gunda |

2,241 |

Norw. |

25⁰ 40'S; 33⁰ 53'E |

|

12 |

19 Nov 1942 (U-177) |

Scottish Chief |

7,006 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 39'S; 34⁰ 41'E |

|

13 |

20 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Corinthiakos |

3,562 |

Greek |

25⁰ 42'S; 33⁰ 27'E |

|

14 |

20 Nov 1942 (U-177) |

Pierce Butler |

7,191 |

Amer. |

29⁰ 40'S; 36⁰ 35'E |

|

15 |

21 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Alcoa Pathfinder |

6,797 |

Amer. |

26⁰ 45'S; 33⁰ 10'E |

|

16 |

24 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Dorington Court |

5,281 |

Brit. |

27⁰ 00'S; 34⁰ 45'E |

|

17 |

24 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Mount Helmos |

6,481 |

Greek |

26⁰ 38'S; 34⁰ 58'E |

|

18 |

27 Nov 1942 (U-178) |

Jeremiah Wadsworth |

7,176 |

Amer. |

39⁰ 25'S; 22⁰ 23'E |

|

19 |

28 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Evanthia |

3,551 |

Greek |

25⁰ 13'S; 34⁰ 00'E |

|

20 |

28 Nov 1942 (U-177) |

Nova Scotia |

6,796 |

Brit. |

28⁰ 30'S; 33⁰ 00'E |

|

21 |

30 Nov 1942 (U-181) |

Cleanthis |

4,153 |

Greek |

24⁰ 29'S; 35⁰ 44'E |

|

22 |

30 Nov -1942 (U-177) |

Llandaff Castle |

10,799 |

Brit. |

27⁰ 20'S; 33⁰ 40'E |

|

23 |

2 Dec 1942 (U-181) |

Amarylis |

4,328 |

Pan. |

28⁰ 14'S; 33⁰ 24'E |

|

24 |

7 Dec 1942 (U-177) |

Saronikos |

3,548 |

Greek |

24⁰ 46'S; 35⁰ 30'E |

|

25 |

12 Dec 1942 (U-177) |

Empire Gull |

6,408 |

Brit. |

26⁰ S; 35⁰ E |

|

26 |

14 Dec 1942 (U-177) |

Sawahloento |

3,085 |

Dutch |

31⁰ 02'S; 34⁰ 00'E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

26 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

138,575 tons |

||||

Table 3.9: Merchantmen lost to the first U-cruiser operation, Oct-Dec 1942[37]

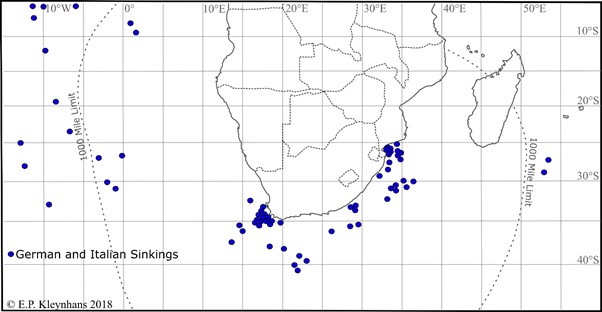

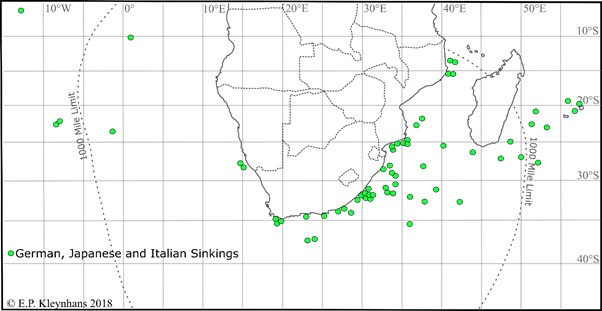

Map 3.3 Shipping lost to German and Italian submarines, 1942

In December, the SKL requested that the BdU maintain pressure along the South African coast. It also ordered a new U-boat operation to continue to harass the shipping along the extended Allied supply routes. The BdU appreciated that the type IXC U-boats, used by the Eisbär group, proved ill-suited for operations in distant waters. Their limited fuel capacity was insufficient even when refuelled along the way by a milch cow, and this significantly reduced their deployment to an operational area. Notwithstanding, the BdU was once more forced to despatch four type IXC U-boats for the operations off Cape Town as no type IXD2 U-boats were available. The BdU assigned U-506 (Würdemann), U-516 (Wiebe), U-509 (Witte) and U-160 (Lassen), to form the core of the Seehund Group, with the milch cow U-459 once more attached to the pack. The U-boats departed from their bases in the Bay of Biscay in December 1942 and January 1943, after which they replenished their supplies from U-459 approximately 600 miles to the south of St Helena Island.

The Seehund group travelled south without incident and arrived in the operational area off Cape Town at the end of January and the beginning of February. The arrival of U-182 (Clausen), the only available type IXD2 U-boat, further bolstered the strength of the Seehund group. The operational conditions in the South African waters had, however, drastically changed since October 1942. The deterioration of these conditions was in part due to the heightened South African and Allied A/S measures, strong radar protection and the introduction of escorted convoys along the South African coast.[38]

The sinking results of the Seehund Group were, however, negligible for the entire time during which the U-boats were operational off the South African coast. During the initial deployment of the Seehund Group between Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, its sinking results were exceptionally poor. During this period, only five ships were sunk: the Queen Anne (4,937 tons), Helmspey (4,764 tons), Deer Lodge (6,187 tons), Llanashe (4,836 tons) and the Dutch submarine tender Colombia (10,782). By the beginning of March, the Seehund group were ordered further eastwards towards the waters off Durban and Lourenço Marques where there was more potential for merchant spoils. During the whole of March, only ten merchantmen were sunk: the Nirpura (5,961 tons), Empire Mahseer (5,087 tons), Harvey W. Scott (7,176 tons), Marietta E. (7,628 tons), Sabor (5,212 tons), James B. Stephens (7,176 tons), Tabor (4,768 tons), Richard D. Spaight (7,177 tons), Aelybryn (4,986 tons), and the Nortun (3,663 tons).

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

10-Feb-1943 (U-509) |

Queen Anne |

4,937 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 53'S; 19⁰ 51'E |

|

2 |

11-Feb-1943 (U-516) |

Helmspey |

4,764 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 22'S; 24⁰ 54'E |

|

3 |

17-Feb-1943 (U-516) |

Deer Lodge |

6,187 |

Amer. |

33⁰ 46'E; 26⁰ 57'E |

|

4 |

17-Feb-1943 (U-182) |

Llanashe |

4,836 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 00'S; 28⁰ 30'E |

|

5 |

27-Feb-1943 (U-516) |

Colombia |

10,782 |

Dutch |

33⁰ 36'S; 27⁰ 29'E |

|

6 |

3-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

Nirpura |

5,961 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 47'S; 29⁰ 47'E |

|

7 |

3-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

Empire Mahseer |

5,087 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 01S; 30⁰ 48'E |

|

8 |

3-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

Harvey W. Scott |

7,176 |

Amer. |

31⁰ 54'S; 30⁰ 37'E |

|

9 |

4-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

Marietta E. |

7,628 |

Brit. |

31⁰ 49'S; 31⁰ 11'E |

|

10 |

7-Mar-1943 (U-506) |

Sabor |

5,212 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 30'S; 23⁰ 10'E |

|

11 |

8-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

James B. Stephens |

7,176 |

Amer. |

28⁰ 53'S; 33⁰ 18'E |

|

12 |

9-Mar-1943 (U-506) |

Tabor |

4,768 |

Norw. |

37⁰ 30'S; 23⁰ 15'E |

|

13 |

10-Mar-1943 (U-182) |

Richard D. Spaight |

7,177 |

Amer. |

28⁰ S; 37⁰ E |

|

14 |

11-Mar-1943 (U-160) |

Aelybryn |

4,986 |

Brit. |

28⁰ 30'S; 34⁰ 00'E |

|

15 |

20-Mar-1943 (U-516) |

Nortun |

3,663 |

Pan. |

27⁰ 35'S; 14⁰ 22'E |

|

16 |

2-Apr-1943 (U-509) |

City of Baroda |

7,129 |

Brit. |

27⁰ 56'S; 15⁰ 21'E |

|

17 |

5-Apr-1943 (U-182) |

Aloe |

5,047 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 37'S; 37⁰ 50'E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

17 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

102,516 tons |

||||

Table 3.10: Merchantmen lost to the Seehund Group, Feb-Apr 1943[39]

By the end of March, the Seehund Group was ordered back to the operational area to the west of Cape Town. On their onward journey towards Port Nolloth and Walvis Bay, only a further two merchant vessels were sunk. These were the City of Baroda (7,129 tons) and Aloe (5,047 tons). Hereafter the U-boats were forced to turn back to their bases as their supplies ran out. During the return voyage, U-182 was sunk by the American destroyer USS Mackenzie on 16 May. The remainder of the U-boats, however, safely reached their bases between 3 and 11 March. It is evident that the sinking results of the Seehund Group were less striking, and indeed convincing, than the results obtained by the Eisbär Group and the first U-cruiser operation during 1942 (see Graph 3.1). Between February and April, the Seehund Group and U-182 sunk a total of only 17 merchantmen, a mere 102,516 tons of shipping (see Table 3.10).[40]

.jpg)

Graph 3.1: Comparative successes of the Eisbär Group, the first U-cruiser operation, and the Seehund Group

By 1943, the main Italian submarine operations were directed against shipping off the Brazilian coast. On 20 February, however, an Italian submarine, the Leonardo da Vinci (Gazzana), left Bordeaux and arrived in South African waters at the beginning of April. During its operational deployment, the Leonardo da Vinci succeeded in sinking five merchantmen: the Lulworth Hill (7,628 tons), Sembilan (6,566 tons), Manaar (8,007 tons), John Drayton (7,177 tons) and the Doryssa (8,078 tons). The Italian submarine was, however, lost during its return voyage through the combined efforts of the British destroyer HMS Active and the frigate HMS Ness (see Table 3.11).[41

|

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

|

1 |

19 Mar 1943 (L. Da Vinci) |

Lulworth Hill |

7,628 |

Brit. |

10⁰ 10's; 01⁰ 00'E |

|

2 |

17 Apr 1943 (L. Da Vinci) |

Sembilan |

6,566 |

Dutch |

31⁰ 30'S; 33⁰ 30'E |

|

3 |

18 Apr 1943 (L. Da Vinci) |

Manaar |

8,007 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 59'S; 33⁰ 00'E |

|

4 |

21 Apr 1943 (L. Da Vinci) |

John Drayton |

7,177 |

Amer. |

32⁰ 10'S; 34⁰ 50'E |

|

5 |

25 Apr 1943 (L. Da Vinci) |

Doryssa |

8,078 |

Brit. |

37⁰ 03'S; 24⁰ 03'E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

5 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

37,456 tons |

Table 3.11: Merchantmen lost to Italian submarine operations, Mar-Apr 1943[42]

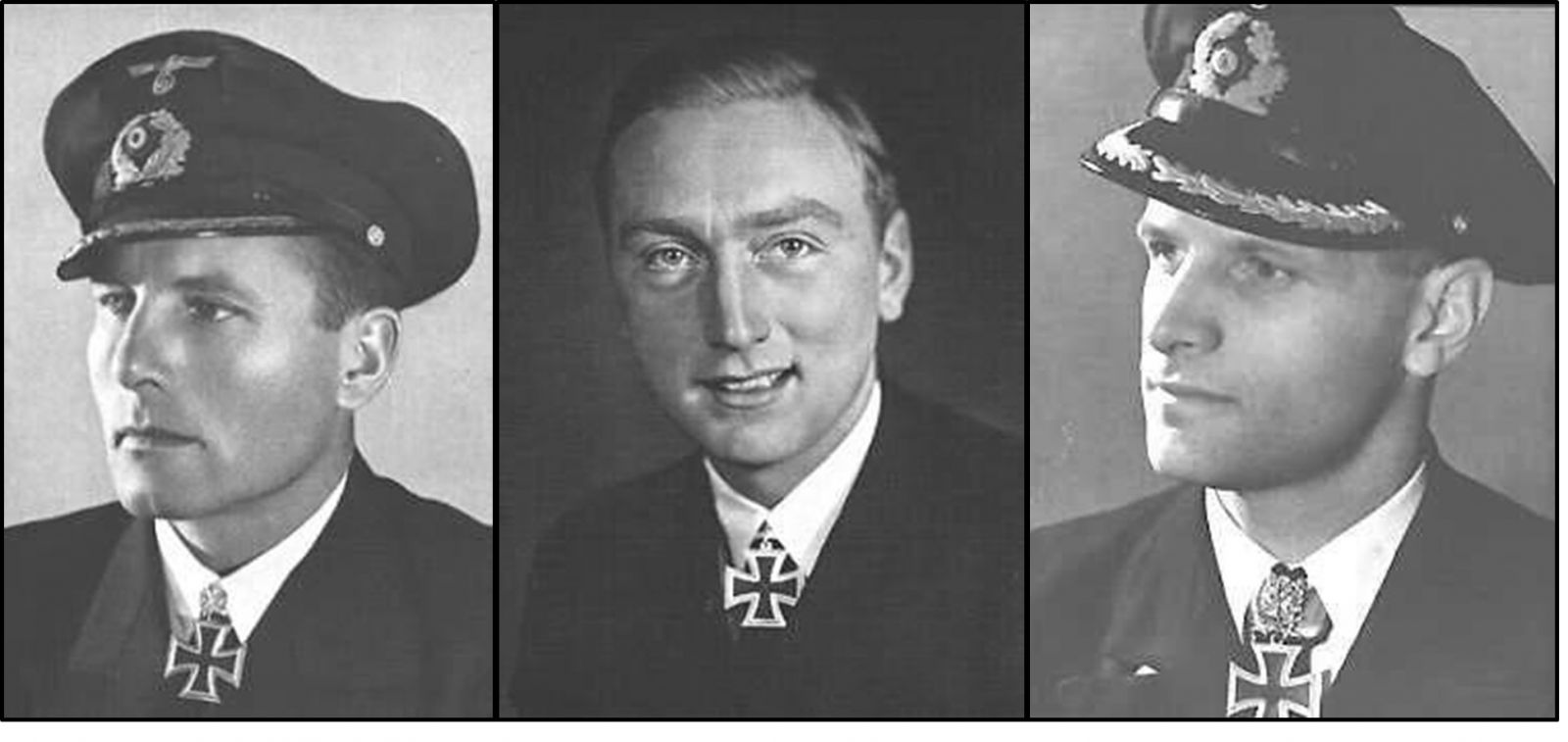

Fig 3.8: The top U-boat aces in South African waters during the war – Karl-Friederich Merten, Wolfgang Lüth, Helmut Witte[43]

By April, only U-182 remained operational off the South African coast. The BdU decided that a large number of IXD U-boats, which had become available during February and March, would be despatched to relieve the Seehund group, and collectively formed part of the second U-cruiser operation in the Southern Oceans. The extended fuel capacity of these U-boats allowed for greater operational freedom in distant waters. On 9 February, U-180 (Musenberg) – one of only two experimental type IXD1 U-boats – left the Bay of Biscay destined for Madagascar. Musenberg was ordered to rendezvous with the Japanese submarine, I-29 (Kinashi) off Madagascar and deliver the Indian dissident Subhas Bose. During her voyage to the rendezvous, U-180 sank the Corbis (8,132 tons) on 18 April. After the successful delivery of Bose on 26 April, U-180 remained operational off the South African coast until 26 May without any further results.[44]

Over the period of 9 April to 3 May, a further nine type IXD2 U-boats made for the operational area in the South African waters. They included U-177 (Gysae), U-178 (Dommes) U-181 (Lüth), U-195 (Buchholz), U-196 (Kentrat), U-197 (Bartels), U-198 (Hartmann), U-402 (Freiherr von Forstner) and U-511 (Schneewind). The first of these U-boats arrived in the operational area towards the end of April, with U-177, U-181, U198 and U-402 sinking a number of merchant vessels between Cape Town and the Mozambique Channel. During May alone, seven merchantmen were sunk by these Uboats. They were the Nailsea Meadow (4,962 tons), Tinhow (5,232 tons), Northmoor (4,392 tons), Sicilia (1,633 tons), Storaas (7,886 tons), Agwimonte (6,697 tons) and the Hopetarn (5,231 tons). The main reason behind the sudden successes appears to have been the greater speed which could be reached by the type IXD2 U-boats. In June, a further five merchantmen were sunk: the Salabangka (6,586), Dumra (2,304 tons), William King (7,176 tons), Harrier (193 tons), and the Sebastian Cermeno (7,194 tons). By the end of that month, the U-boats had replenished their stores from the German surface tanker, the Charlotte Schliemann, well to the south of the island of Mauritius.[45]

After restocking, the U-boats relocated to new operational areas, which saw the submarines working towards the east coast of South Africa in a quadrant between Durban, Lourenço Marques, the Mozambique Channel, Mauritius and Madagascar. This new operational area at once proved more profitable, with the U-boats sinking a further 14 merchantmen.[46] Included were the Michael Livanos (4,774 tons), Breiviken (2,669 tons), Hydraios (4,476 tons), Jasper Park (7,129 tons), Leana (4,743 tons), Alice F. Palmer (7,176 tons), Mary Livanos (4,771 tons), Robert Bacon (7,191 tons), City of Canton (6,692 tons), Pegasus (9,583 tons), Mangkalihat (8,457 tons), City of Oran (7,323), Efthalia Mari (4,195 tons) and the Empire Stanley (6,921 tons) (see Table 3.12).[47]

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

18-Apr-1943 (U-180) |

Corbis |

8,132 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 56'S ; 34⁰ 03'E |

|

2 |

11-May-1943 (U-402) |

Nailsea Meadow |

4,962 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 04'S ; 29⁰ 13'E |

|

3 |

11-May-1943 (U-181) |

Tinhow |

5,232 |

Brit. |

25⁰ 15'S ; 33⁰ 30'E |

|

4 |

17-May-1943 (U-198) |

Northmoor |

4,392 |

Brit. |

28⁰ 27'S ; 32⁰ 43'E |

|

5 |

27-May-1943 (U-181) |

Sicilia |

1,633 |

Swed. |

24⁰ 31'S ; 35⁰ 12'E |

|

6 |

28-May-1943 (U-177) |

Storaas |

7,886 |

Norw. |

34⁰ 57'S ; 19⁰ 33'E |

|

7 |

28-May-1943 (U-177) |

Agwimonte |

6,697 |

Amer. |

34⁰ 57'S ; 19⁰ 33'E |

|

8 |

29-May-1943 (U-198) |

Hopetarn |

5,231 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 50'S ; 39⁰ 32'E |

|

9 |

1-Jun-1943 (U-178) |

Salabangka |

6,586 |

Dutch |

31⁰ 08'S ; 31⁰ 18'E |

|

10 |

5-Jun-1943 (U-198) |

Dumra |

2,304 |

Brit. |

28⁰ 15'S ; 33⁰ 20'E |

|

11 |

6-Jun-1943 (U-198) |

William King |

7,176 |

Amer. |

30⁰ 25'S ; 34⁰ 15'E |

|

12 |

7-Jun-1943 (U-181) |

Harrier |

193 |

Brit. |

25⁰ 50'S ; 33⁰ 20'E |

|

13 |

27-Jun-1943 (U-511) |

Sebastian Cermeno |

7,194 |

Amer. |

29⁰ 00'S ; 50⁰ 10'E |

|

14 |

4-Jul-1943 (U-178) |

Michael Livanos |

4,774 |

Greek |

22⁰ 52'S ; 36⁰ 47'E |

|

15 |

4-Jul-1943 (U-178) |

Breiviken |

2,669 |

Norw. |

21⁰ 50'S ; 37⁰ 50'E |

|

16 |

6-Jul-1943 (U-198) |

Hydraios |

4,476 |

Greek |

24⁰ 44'S ; 35⁰ 12'E |

|

17 |

6-Jul-1943 (U-177) |

Jasper Park |

7,129 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 52'S ; 42⁰ 15'E |

|

18 |

7-Jul-1943 (U-198) |

Leana |

4,743 |

Brit. |

25⁰ 06'S ; 35⁰ 33'E |

|

19 |

10-Jul-1943 (U-177) |

Alice F. Palmer |

7,176 |

Amer. |

26⁰ 30'S ; 44⁰ 10'E |

|

20 |

11-Jul-1943 (U-178) |

Mary Livanos |

4,771 |

Greek |

15⁰ 40'S ; 40⁰ 45'E |

|

21 |

14-Jul-1943 (U-178) |

Robert Bacon |

7,191 |

Amer. |

15⁰ 25'S ; 41⁰ 13'E |

|

22 |

16-Jul-1943 (U-178) |

City of Canton |

6,692 |

Brit. |

13⁰ 52'S ; 41⁰ 10'E |

|

23 |

23-Jul-1943 (U-197) |

Pegasus |

9,583 |

Swed. |

28⁰ 05'S ; 37⁰ 40'E |

|

24 |

1-Aug-1943 (U-198) |

Mangkalihat |

8,457 |

Dutch |

25⁰ 06'S ; 34⁰ 14'E |

|

25 |

2-Aug-1943 (U-196) |

City of Oran |

7,323 |

Brit. |

13⁰ 45'S ; 41⁰ 16'E |

|

26 |

5-Aug-1943 (U-177) |

Efthalia Mari |

4,195 |

Greek |

24⁰ 21'S ; 48⁰ 55'E |

|

27 |

17-Aug-1943 (U-197) |

Empire Stanley |

6,921 |

Brit. |

27⁰ 08'S ; 48⁰ 15'E |

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

27 |

||||

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

153,718 tons |

||||

Table 3.12: Merchantmen lost to the second U-cruiser operation, Apr-Aug 1943[48]

Between 8 and 20 August, the U-boats used up most of their supplies and were obliged to return home. During this period, U-197 was lost after being bombed by Allied aircraft just south of Madagascar on 20 August. The remaining U-boats had arrived in Bordeaux by mid-October. Between 18 April and 17 August, the U-boats of the second U-cruiser operation accounted for 27 merchant ships sunk, totalling 153,718 tons of shipping lost. Despite more active South African and Allied counter-measures, Dönitz’s U-boats managed to sink 44 merchant ships off the coast of South Africa during the whole of 1943, amounting to a total of 256,243 tons of shipping lost. In October, the Faneromeni (3,404 tons) was sunk by the Japanese submarine I-37 in the Mozambique Channel. This was the last merchantman lost in South African waters for the year 1943. The Italian and Japanese submarines added six more merchantmen to this tally, amounting to a further 40,860 tons of shipping lost. Altogether the Axis submarine offensives accounted for 50 merchant vessels sunk in 1943, totalling 297,103 tons of shipping lost.[49]

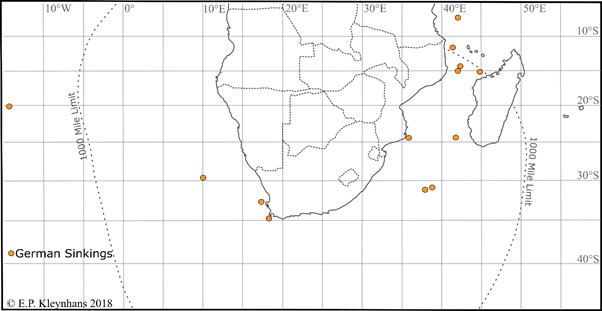

Map 3.4: Shipping lost to Axis submarines, 1943

For the remainder of the Second World War, more notably from September 1943, the BdU ceased to regard the region off the South African coast as a viable operational area. It argued that the submarines earmarked for offensive operations in the Far East would have to pass through South African waters before they could reach their fareastern bases at Penang and Surabaya. This would provide the U-boats with ample opportunity to attack Allied merchant shipping along the South African coastline during their journeys to and from the east. The A/S measures had become so efficient around the South African coast – especially the well-organised air patrol service by the SAAF and Royal Air Force – that the U-boats found it increasingly difficult to operate successfully against merchant shipping.

There were, however, exceptions to the rule.[50] During the course of 1944, four U-boats, U-862 (Timm), U-852 (Eck), U-198 (Waldegg) and U-861 (Oesten), managed to sink eight Allied merchant ships, accounting for 42,267 tons of shipping lost. The merchant vessels that had been sunk comprised of the Dahomian (5,277 tons), Columbine (3,268 tons), Director (5,107 tons), Radbury (3,614), Empire Lancer (7,037 tons), Nairung (5,414 tons), Wayfarer (5,086 tons) and the Berwickshire (7,464 tons). The Point Pleasant Park (7,136 tons) was sunk by U-510 (Eick) on 23 February 1945. This was the last Allied merchantman sunk off the South African coast during the war (see Table 3.13).[51]

|

# |

Date Attacked On/By |

Ship |

Tonnage |

Country |

Lat/Long |

|

1 |

1 Apr 1944(U-852) |

Dahomian |

5,277 |

Brit. |

34⁰ 25'S ; 18⁰ 19'E |

|

2 |

16 Jun 1944(U-198) |

Columbine |

3,268 |

Brit. |

32⁰ 44'S ; 17⁰ 22'E |

|

3 |

14 Jul 1944(U-198) |

Director |

5,107 |

Brit. |

24⁰ 30'S ; 35⁰ 44'E |

|

4 |

13 Aug 1944(U-862) |

Radbury |

3,614 |

Brit. |

24⁰ 20'S ; 41⁰ 45'E |

|

5 |

16 Aug 1944(U-862) |

Empire Lancer |

7,037 |

Brit. |

15⁰ S ; 45⁰ E |

|

6 |

18 Aug 1944(U-862) |

Nairung |

5,414 |

Brit. |

15⁰ S ; 42⁰ E |

|

7 |

19 Aug 1944(U-862) |

Wayfarer |

5,086 |

Brit. |

14⁰ 30'S ; 42⁰ 20'E |

|

8 |

20 Aug 1944(U-861) |

Berwickshire |

7,464 |

Brit. |

30⁰ 58'S ; 38⁰ 50'E |

|

9 |

23 Feb 1945 (U-510) |

Point Pleasant |

7,136 |

Brit. |

29⁰ 42'S ; 09⁰ 58'E |

|

|

Total Merchants Sunk |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Tonnage Lost |

49,403 tons |

Table 3.13: Merchantmen lost to German U-boats, 1944-1945[52]

Map 3.5: Shipping lost to German U-boats, 1944-1945

[1] Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, pp. 149,152.

[2] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled, by Dr Jurgen Rohwer, 1954; Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, pp. 176-177] https://www.awesomestories.com/images/user/26ccc15ca95b2329dae33452c36a6a27.jpg (Accessed 6 March 2018).

[4] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters, compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[5]http://www.conspiracy-cafe.com/apps/blog/show/42936580-u-196-the-mystery-continuesgold-bullion-uranium-loot (Accessed on 6 March 2018).

[6] Regia Marina Italiana – The Italian Navy in World War II (Website Accessed on 9 May 2017) http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text_with_list.asp?nid=84&lid=1&cid=13.

[7] Regia Marina Italiana – The Italian Navy in World War II (Website Accessed on 9 May 2017) http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text_with_list.asp?nid=84&lid=1&cid=21.

[8] Regia Marina Italiana – The Italian Navy in World War II (Website Accessed on 9 May 2017) http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text_with_list.asp?nid=84&lid=1&cid=42.

[9] Regia Marina Italiana – The Italian Navy in World War II (Website Accessed on 9 May 2017) http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text_with_list.asp?nid=84&lid=1&cid=44.

[10] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters, compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[11] Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, pp. 237-238; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[12] https://za.pinterest.com/pin/36099234497206289/ (Accessed on 6 March 2018)

[13] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[14] Statistical data collated from the website Uboat.net, especially the individual pages dealing with the various U-boats types used during the Second World War (http://uboat.net/types/). Website accessed on 5 June 2017; data verified where possible with Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 257.

[15] Also known as U-tankers, these boats were used to replenish wolf packs while operational. The U-tankers carried spare parts, a doctor, technicians, food stores, ammunition and extra fuel oil, which they used to replenish U-boats upon instruction from the BdU. See DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Report on experience gained by U-459 refuelling 15 U-boats, 21 Mar – 15 May 1942; Busch, U-Boats at War, pp. 144–145; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 158.

[16] Doenitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, pp. 276–283; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[17] https://i.pinimg.com/originals/63/cb/4c/63cb4c85b064964801aedc05d462a4e1.jpg; https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e4/6b/57/e46b57467a65f1221dd4ec9fc3e2a04f.jpg (Accessed on 6 March 2018).

[18] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Operation Order “Eisbär”, 1 Aug 1942; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Report on experience gained by U-459 refuelling 15 U-boats, 21 Mar – 15 May 1942; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Report on U-boat policy & ops in South African waters by Walter Meyer.

[19] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Report on U-boat policy & ops in South African waters by Walter Meyer.

[20] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[21] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 161-167.

[22] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:U-156_37-35_Laconia_1942_09_15.jpg (Accessed on 6 March 2018).

[23] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954.

[24] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Extracts from war diary U-159 (Helmut Witte), 24 Aug 1942 – 5 Jan 1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Comments on war diary U 159 (Helmut Witte); DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Report on my experiences on board U-68 on voyage to Cape Town from middle of August to middle of December 1942 by Walter Meyer.

[25] https://za.pinterest.com/pin/228839224799411632/ (Accessed on 6 March 2018).

[26] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[27] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[28] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Emmermann (U-172) on Operation Eisbär; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Report on my experiences on board U-68 on voyage to Cape Town from middle of August to middle of December 1942 by Walter Meyer.

[29] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Extracts from War Diary U-159 (Helmut Witte) – 24 Aug 1942-5 Jan 1943; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat material. Comments on War Diary U-159 (Helmut Witte).

[30] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[31] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: Long naval history

[32] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters, compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954.

[33] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[34] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 189-201.

[35] Regia Marina Italiana – The Italian Navy in World War II (Website Accessed on 5 June 2017).http://www.regiamarina.net/detail_text_with_list.asp?nid=84&lid=1&cid=12

[36] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[37] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 340, File: Long naval history

[38] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 341, File: U-boat matters. Questions and answers submitted by UWH section to Fregattenkapitän Gunter Hessler re U-boat warfare in South African waters.

[39] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 340, File: Long naval history

[40] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[41] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters, compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954.

[42] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 340, File: Long naval history. Ships lost or damaged by enemy action in South African waters.

[43]https://uboat.net/men/merten.htm; https://uboat.net/men/luth.htm; https://uboat.net/men/witte.htm (Accessed on 6 March 2018).

[44] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 342, File: Newspaper Articles Naval War. ‘Gold gab für man Bose’ in Muenchner Illustrierte, 13 Mar 1954; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954.

[45] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[46] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 219-237; DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954.

[47] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[48] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 340, File: Long naval history. Ships lost or damaged by enemy action in South African waters.

[49] Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, p. 240; Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, p. 83.

[50] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 220, File: Union War Histories Translations 14a. U-boat Operations of the Axis Powers in S.A. Waters compiled by Dr Jürgen Rohwer, 1954; Turner et al, War in the Southern Oceans, pp. 238-255.

[51] Gordon-Cumming, Official History of the South African Naval Forces, pp. 287-299; DOD Archives, Map Collection, File: War in the Southern Oceans maps. Chart and List of Ships Sunk Captured or Damaged in the Waters off Southern Africa, 1939-1945.

[52] DOD Archives, UWH Civil, Box 340, File: Long naval history. Ships lost or damaged by enemy action in South African waters.