U.S. NAVY VP SQUADRONS IN BRAZIL - THE TIMES OF RICHARD ARNOLD AT VP 94

4)NEXT CHALLENGE BRAZIL AND VP 94

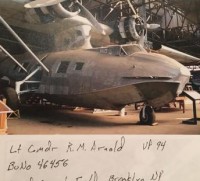

We checked in at Norfolk expecting to be assigned to those B-25 squadrons we had trained for. Don got orders to a B-24 (Navy designation PB4Y-l) squadron operating out of England. My orders directed me to report to VP-94. One of their pilots was in Norfolk picking up a new airplane for the squadron. When I reported to him, I found out what I would be flying. It was technically a land based bomber - actually it was an amphibian. PBY-5As were large, slow, high winged, twin engine airplanes whose cruising speed was about 100 knots. The good news was we did fly them off land since I had never flown anything off water.

I met Lt. John Batchelder and he told me to be ready to fly a test flight with him the next day, hopefully to accept the airplane for the squadron and head for the South Atlantic immediately. On November 24, 1943, I had my first flight in a PBY. There was a third pilot with me but I don’t have any recollection of who it was. On the test flight, I flew co-pilot to Batchelder. I had no idea what my responsibilities were and he made no effort to tell me, so when he pushed the throttles forward and started down the runway, I was enjoying myself looking out the window. When we got in the air, I looked over and his hands were flying all over the cockpit. He had neglected to tighten the friction lock on the throttles and every time he took his hand off to reach for the gear handle, they would creep back. He would have to grab them again and couldn’t get the gear up. I finally realized he needed help so I blocked the throttles and everything was fine from then on.

The plane was acceptable so we got everyihing signed off and got ready to leave. Actually we didn’t leave till the 27th. On the 27th, we departed for Jacksonville, stayed overnight and left the States the next day. I was the third pilot and finally had to navigate an airplane over water for real. I can still remember thinking My God, I hope he knows where he is going. He accepted all my instructions and headings time - in more ways than one! As slow as PBYs were, we only went 600 to 800 miles a day. We were not supposed to fly in bad weather when transporting a new plane. However, if the weather stayed bad too long, we would just clear out operational and go on our way. We carried four 350 pound depth charges under our wing so that let us go whenever we indicated it could be a submarine search. Our next leg took us to San Juan, Puerto Rico, then on to Georgetown, British Guiana.

On that leg we flew over the castle of the mad king, Henri Christophe, who used to show how well disciplined his troops were by marching them off a cliff. Probably couldn’t understand why his recruiting efforts were doing poorly. The final leg was almost eleven hours over Dutch and French Guiana with a low pass over Devils Island which was no longer used as a penal colony. We flew over it at about twenty to thirty feet so we could see the cells in the ground. It didn’t look like a great place to spend your life. As we got closer to our base, which was Belem, Brazil, we received a message to initiate a search for one of the squadron planes that had failed to return from a patrol a day or so before. That was my introduction to Ted Stritter and his co-pilot named Bauer. Unfortunately, they were already dead. We didn’t find any wreckage or any other debris that gave any indication of what happened to them.

A few days later one of the squadron planes found a wing-tip float and part of the navigation table washed up on a beach north of our base. None of the crew was ever found I flew a short test flight the next day and then my first ten hour patrol the day after that. We were still searching for survivors or wreckage, so part of it was search and part submarine hunt. I guess it dawned on me then that bad things can happen when you are in a big underpowered Navy airplane hundreds of miles out over the ocean. The squadron had been down there over a year and hadn’t lost too many people. They had also sunk several subs and had lost one pilot, Frank Hare, from gun fire from a sub. The subs had learned that if they were caught on the surface, they would man their 20 MM deck gun and machine guns and shoot it out. Hare was killed by a cannon shell through the instrument panel.

His co-pilot Frank McMacken finished the run and dropped the bombs on the sub. He had to fly the badly damaged plane through bad weather without instruments back to the base. I flew with several different plane commanders for a while. There had been some other new pilots join the squadron about the same time as I did so we were all being passed around for evaluation. Frank Clark had come from nav school, Ray Neal became my roommate later, Steve Hall, and Red Johnson were all pretty new. I flew with Don Faulkner, Jack Carlson, Carl Spaeth, and some others. I was finally assigned to Jack Carlson, Don got Frank Clark. We flew patrols or convoy coverage about every three days when either of the two were in the area. We would go north as far as the Guianas and bring the convoys down to about Recife then about half way to Ascension Island. At that point a B-24 squadron from Ascension would pick it up and take it the rest of the way across.

Our first base, Belem was just south of the equator, one degree of latitude to be exact. That is sixiy nautical miles. So on every patrol we would cross the equator many times. Belem was also sixty miles from the mouth of the Amazon River, so in bad weather if we could find the river we had it made. There was always an equatorial front around there and some of the older pilots, from the standpoint of time there, had gotten a little shakey about weather flying. I had an experience with two of them later on. As new co-pilots we were checked out in the airplanes just as we had been in all the planes we had flown previously. On my first flight in the left seat, I got a chance to show that I knew how to fly. I was being checked out by a plane commander named Clancy Armenaki. We had taken off, flown around a little to let me get the feel of the airplane and gone back to shoot some landings.

On downwind leg, I noticed a circle of large birds right off the end of the runway - right where I was going. I pointed it out to Clancy and he said they were always there and would get out of the way, just go on in and land. As I turned on final, they were still there. I lined up with the runway and at about 200 feet, a buzzard hit the windshield. The body came through the right side, where Clancy was, showering him with glass. He was unable to see and started grabbing for the throttles, controls and anything else. I got him to let things alone and made my first landing with the buzzard’s wings spread clear across the windshield. It was a good landing and didn’t hurt my reputation as a co-pilot.

When we had no convoys or subs in the area, we flew training flights as did the plane commanders. We practiced instrument flying, low level bombing, take-off and landing and anything else we needed to keep us sharp. Two co-pilots could go out together on a training flight without a senior pilot. Paul Bradley had been an instructor in PBYs but still had to go through the same routine as we did. He was a full lieutenant but wasn’t any closer to plane commander than I was. We became roommates and Brad was one of my best friends in the squadron as well as later. When we went out on convoy coverage, we would head for a position fairly close behind the Convoy’s track. Usually you could see the wakes of the ships. We would fly up the wake, locate the plane we were relieving, contact them by blinker and relieve them. They would head home and we would take over.

We immediately went down and circled the lead ship, checked positions again by blinker and started our patterns. We did not just fly circles around the convoy, there was a pattern which kept us fairly close to all parts of it. If we saw a problem we could head for that location immediately. Occasionally we could see the destroyers or destroyer escorts drop depth charges on a suspected contact. We could not drop unless we saw a periscope or a sub. We were unable to see a submarine under water. We had an airplane over a convoy twenty-four hours a day when they were in our area. The squadron had a great record and never lost a ship out of a convoy their entire deployment. We were later recommended for a presidential citation. However, we had a new skipper who came to us from the Pacific. He had flown the last PBY out of the Philippines and was in a real war. He turned the citation down. He didn’t think what we did was all that great.

When our relief showed up, we could head for home. There were twenty or thirty ships in most of the convoys so we could not leave them unprotected. Most of the flights were routine and pretty dull. Occasionally we were vectored someplace where there was trouble, but rarely found any. One time I was sent out with Al Ansellmo. He had just received his designation as a plane commander (PPC) and it was his first patrol as pilot in command. We were flying at about 200 feet coming around the back of the convoy. All of a sudden we both saw what appeared to be a periscope behind one of the ships. Al jammed the throttles forward and I hit the arming switches and alerted the gunners. Just as suddenly I realized it was a whale, disarmed the bombs and told Al not to drop.

There were several whales following the convoy, probably waiting for lunch. Could have been embarrassing. Later we saw something else that we almost made a run on. To say that Al was ready for anything is an understatement. It was an exciting patrol for all of us but actually nothing happened. There were times that crews were sent to other bases up or down the coast to shorten our flights to the convoys. We went to towns like Amapa, Sao Luiz, Recife, Bahia or Fortaleza. We also operated off the island of Fernando de Noronha about two hundred miles out in the Atlantic. The vweather was terrible out there. It poured down so hard that we could only see a few hundred feet down the runway on take-off. The runway was cut between two small hills and there was one off the end of the runway in the water for good measure. We would line the airplane up on the runway heading, set the compass and pour on the coal.

We could see about two or three runway lights ahead of us and when we were in the air, it was total blackness. It was bad enough going out of there, but trying to find it coming back was something else. We came back one time in bad weather and were on solid instruments with no radio aids. We had hit a couple of holes in the overcast where we could shoot a sun line with our octant. We each took one at different times and all three showed us about sixty miles from our DR position. I was the last one to take one and I told Jack that if we were all right about the position of our sunlines, we were even with the island then, but we didn’t know which side we were on. About that time, we hit a hole in the overcast and the island was off our right wing. If we hadn’t seen it, we would have had to try for the coast, but we did get in.

Jack was a good pilot and we trusted each other. I never worried too much about anything because I felt that Jack could handle any situation. Little did I know that he sort of felt the same way. He bad been developing a good case of nerves and conditions on the island brought it to a head. We had to fly back to the mainland and rejoin the rest of the squadron in a new location - Bahia. On the way back, I was navigating, Jack was flying in the left seat, and our third pilot who shall remain nameless because I don’t remember who he was, was in the right seat. We were in bad weather again and I was tracking Jack who was zigzagging around trying to get around it. Suddenly he jumped out of the seat back into the nav area and told me to get up in the left seat. We usually rotated but inbad weather he stayed in the cockpit.

I said I would show him where we were but he said he’d figure it out and wanted me up there immediately. When I got in the seat, he asked ifl wanted a heading direct to Recife or wanted to try to get around the weather like he had been doing. I didn’t see any way around it so asked for a direct heading. He figured a heading and we flew directly to Recife then on to Bahia. I knew that Jack had a problem.

Cont.